De Blasio takes new tact after latest grand jury decision

Eric Garner and Akai Gurley were black men killed by New York City police officers. Although both deaths provoked anger in the city’s minority communities and renewed debate about policing in the nation’s largest city, the grand juries in each case brought different outcomes, with one officer indicted, one not.

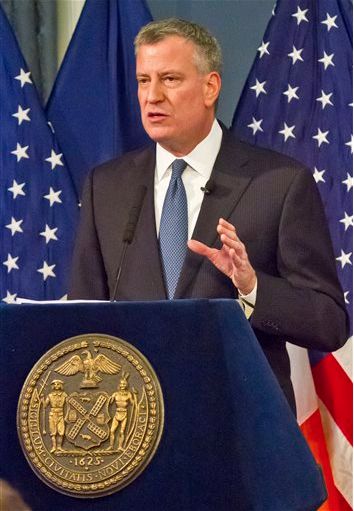

And there was another striking difference: the public reactions from Mayor Bill de Blasio.

De Blasio was emotional and pained in December after a grand jury declined to indict an officer for placing Garner in a fatal chokehold, but he was cool and restrained last week when the officer who shot Gurley in a darkened stairwell was charged with manslaughter. That measured response may have helped the mayor maintain the uneasy truce he has struck with a police force that recently rebelled against him.