Brooklyn Raves: An escape for some, a nuisance for others

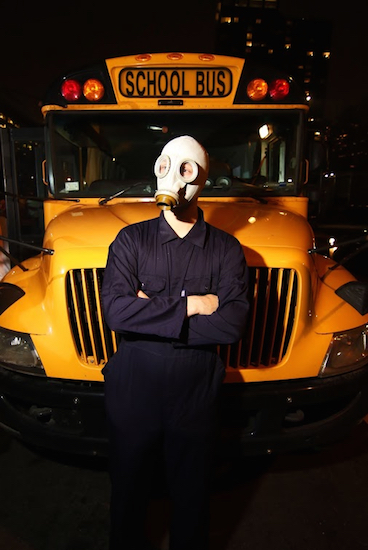

A masked figure in charge of loading blindfolded ravers onto a bus keeps watch. Photos: Daniel Leinweber for Razberry Photography / www.razberryphotography.com

Deafening music. Blinding lights. Decrepit buildings.

This is a typical weekend for many of New York’s youth who choose to dance for hours on end in a trance at Brooklyn’s raves.