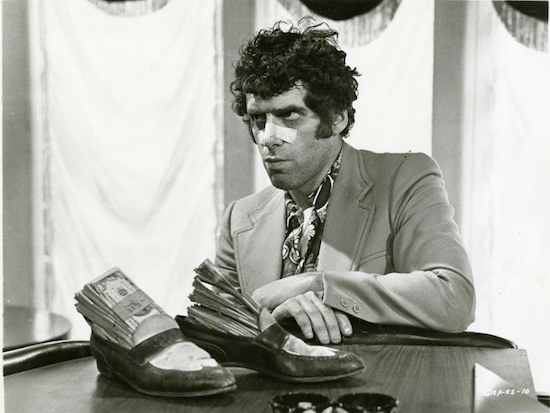

Elliott Gould: Part two of the Brooklyn Eagle’s long-ranging interview

In early June, the Brooklyn Eagle published the first half of an interview with Brooklyn-born actor Elliott Gould. The following is the second half of the interview.

Eagle: Let’s move on to the films and start with 1969’s “Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice.” Because it was only your second leading role in a studio picture (after “The Night They Raided Minsky’s”) and because of the daring subject matter (swinging, wife-swapping, etc.), did you have any reservations about doing it?

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.