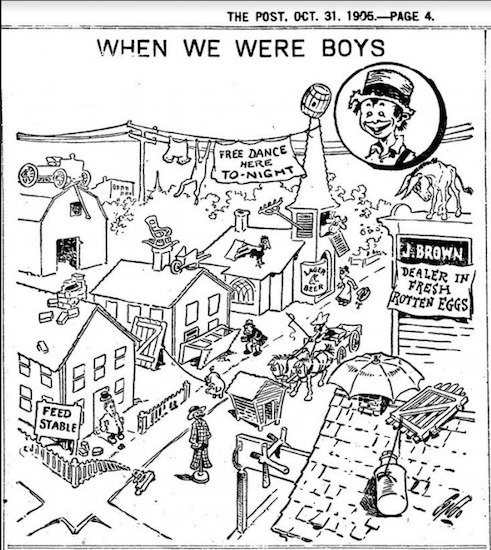

Scary Brooklyn: Recalling Halloween in old Brooklyn

History Of A Day

While the Celtic priests may have originated Halloween centuries ago, Brooklyn has assisted in making the day before All Saints’ Day, aka All Hallows Day, a national costumed event. Of course, it starts with creative types fashioning their individual outfits months before the leaves spin from the trees.

Wasn’t always so. As you may have suspected, the day had religious associations related to the good guys (Christians) against the Bad Guy (The Devil). Victorian Brooklynites saw the day as an introduction to the holiday season. And they had to be more creative than today; they couldn’t just go shopping at Ricky’s.

As today, they had parties to celebrate; the Brooklyn Daily Eagle printed announcements of dinner parties sometimes lasting until dawn, suggesting they were wilder as well as longer than today’s festivities. In 1921, a Ladies’ Night Halloween Party at The Bossert featured costumes and prizes. Presumably the guests escorted the goblins home to the strains of “Danse Macabre.”

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.