OPINION: Waterfront streetcar plan has obstacles to overcome, despite de Blasio’s boost

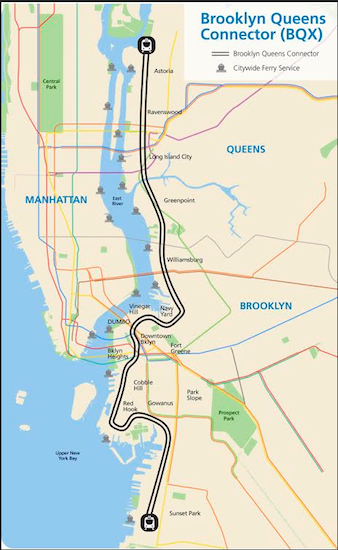

On Feb. 4, as readers of this site know, Mayor Bill de Blasio endorsed a proposal (first reported by the Eagle about a year ago) to build a streetcar line between Astoria and Sunset Park, serving the Brooklyn and Queens waterfront.

With the mayor’s endorsement, a plan that has been bubbling under the surface for a year or two has suddenly taken center stage.

The $2.5 billion plan, known as the Brooklyn Queens Connector, is the project of a nonprofit called, appropriately, the Friends of the Brooklyn Queens Connector. It has some heavy hitters on its board, such as Doug Steiner, Fred Wilson and Helena Durst. A study of the project was spearheaded by well-known traffic planner Sam “Gridlock Sam” Schwartz.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.