Seeing Brooklyn through a lens darkly

Q&A with Jeff L. Rosenheim, Curator in Charge, Department of Photographs, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, on the Occasion of the Exhibition ‘Diane Arbus: In the Beginning 1956-1962’ on View at The Met Breuer Through November 2016

The Roman playwright Terence famously wrote, “Nothing human is foreign to me.” Closer to home, and in a similar vein, our own Walt Whitman counseled, “Be curious, not judgmental.” Looking at the remarkable, early photographs in the Met Breuer’s stunning exhibition “Diane Arbus: In the Beginning,” it seems evident that Arbus was working from Terence’s and Whitman’s playbook.

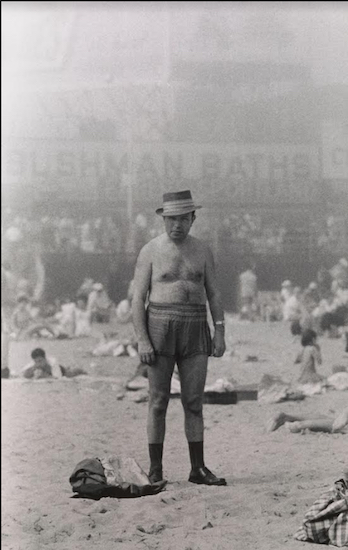

Like Whitman, Arbus embraced multitudes. And among those multitudes was a fair sampling of Brooklyn kooks, oddballs and eccentrics. In fact, Brooklyn, in particular Coney Island, was her favorite outer-borough locale.

“Arbus instinctively understood that photography is a medium that implicates the viewer,” Jeff L. Rosenheim, the Met’s curator in charge, Department of Photographs, told me in an interview conducted shortly after the exhibition’s opening. “In photography, we, as viewers, are the transgressors. We look in the hope of being transformed. Arbus’ photographs are teaching us about who we are. They are a mirror.”

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.