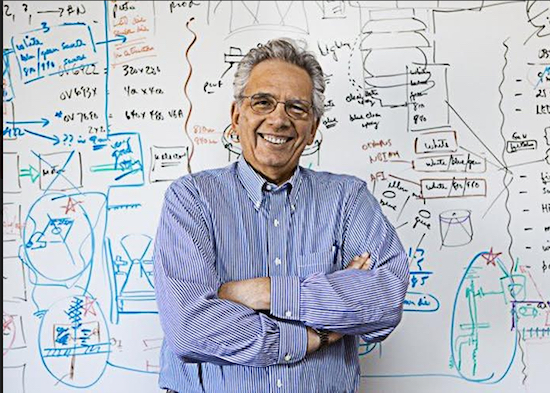

Brooklyn native, co-inventor of DSL, distinguished engineer Richard Gitlin teaches at University of South Florida in Tampa

Brooklynites In Florida

Visionary engineer Richard Gitlin was born in 1943 at Unity Hospital (previously on St. John’s Place until it closed down in 1978) in Brooklyn. Gitlin’s family lived at 648 Bradford St. in East New York in a small, classic, two-story brick building with arched doorways. When he was 2 years old, the family moved to 4211 Seagate Ave. near the western tip of Coney Island. When he was 9, his family moved again to 2455 Haring St. in Sheepshead Bay, where he would live until he entered graduate school at Columbia University.

As the oldest child in a family of four living in a one-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn, Gitlin would watch NBC’s “Mr. Wizard” and create scientific experiments in the only laboratory he had — his mind.

Academically ahead of his class, Gitlin graduated from James Madison High School at 15 and entered City College of New York the next year as an Electrical Engineering major. After earning an MS and his Doctorate from Columbia University, Gitlin worked as an engineer at Bell Labs for 32 years, where he co-founded DSL and eventually became an SVP for communication science research, managing a research team of more than 600 engineers. DSL was the revolutionary technology that changed the data communications industry by allowing for a dramatic increase in the amount of data-per-second transmitted via copper telephone wire, so that data could be more cost effectively uploaded and downloaded in a home or business.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.