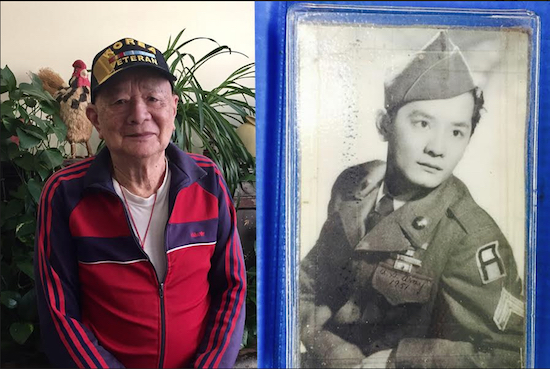

Chinese-born U.S. vet survived critical language barrier

It has been 16 years since he started his clothing business on the sidewalk of Eighth Avenue in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. His store — a 5-foot-long foldable table with a metal hanger on top — sells 1990s-style women’s and men’s clothes. Although the fruit stand across from him changed its owners from Lee to Wong to Gao, he remained at the same spot.

Every morning, Lai Fa Hom, 89, and his wife park their car within view of the clothing stand — next to a fire hydrant — at the corner of 57th Street, where he says he doesn’t get fined.

“Sometimes I run the red light or double-park. The police don’t give me tickets,” Hom said. The reason, he said, is the veteran certificate he carries everywhere he goes. More than half of a century ago, the U.S. Army sent Hom to the Korean War battlefield. The Chinese Army was one of the enemies. Worrying that Hom, a Chinese immigrant, would trade information with the Chinese, the U.S. Army placed him in the artillery division up in the mountains, away from Chinese soldiers.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.