Book tracks Iranian-American family’s year in Iran

Brooklyn BookBeat

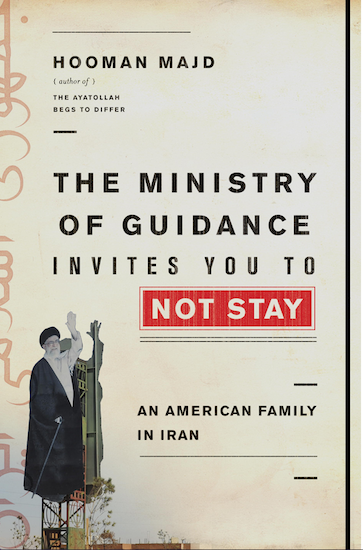

Former Brooklynite Hooman Majd has recently published “The Ministry of Guidance Invites You to Not Stay: An American Family in Iran” (Doubleday), a book about spending a year in Iran with his family. The book arrives in bookstores just as Americans’ interest in the country may be picking up. In September, for the first time in more than three decades, the presidents of both countries spoke by phone. Now, renewed talks about Iran’s contested nuclear program are making news.

Majd, author of two other books about the country, couldn’t have known things would take such a turn when in 2011 he moved from Brooklyn to Tehran to introduce his wife and 8-month-old son to the country where he was born. Still, Majd understands more about Iran than most Westerners, who may just know about the Iran hostage crisis or have seen last year’s blockbuster “Argo.” Majd, in contrast, was born in Tehran in 1957. And while he spent his young life abroad, his family has strong ties to the country. Majd’s father was a diplomat. His maternal grandfather was an ayatollah. And he’s related by marriage to the family of Mohammad Khatami, Iran’s president from 1997 to 2005.

By the time Majd arrives in Iran for his family’s yearlong stay, however, Khatami is out and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is in. Despite his government contacts, Majd isn’t allowed to work while in the country. And though he’s a journalist, he isn’t even supposed to write.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.