Review and Comment: Paris, and Beyond

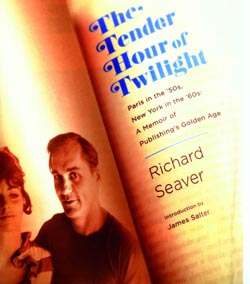

Here was this regular American guy, athletic, with a laconic Yankee sense of humor. Who would have thought he was not only fluent in French and Spanish but had a Ph. D. from the Sorbonne, could quote passages of James Joyce (from Finnegans Wake, no less), knew Samuel Beckett (whom he introduced to America), Jean-Paul Sartre, Eugene Ionesco, Jean Genet, Henry Miller, Brendan Behan, Orson Welles, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg… Richard Seaver, who rarely alluded to any of this, has now had his memoir The Tender Hour of Twilight published posthumously. If he had only lived to see it in print, I would have known to call him by a title he secretly liked, “Coach.”

Years ago, when I played tennis regularly in Central Park, I would notice a woman who looked like a young Elizabeth Taylor playing a court or two away. Between points I would steal glances at her. Some time later I would read about a book editor named Richard Seaver, who had, with his older son, built a tennis court on eastern Long Island.

When I was really on I could beat Dick, but more often he won. A left-hander, he countered my attacks with consistency, fleetness afoot and often startling returns. Sitting down before changing ends of the court, we would chat briefly, and here and there I would get intimations of his rich and varied life and career.

Even so, the memoir is an eye-opener. Here one learns that he had served in the Navy, as supposedly an engineering officer, at the end of World War II; later taught English and Latin at a Connecticut prep school, where, having been a college wrestler, he briefly but successfully served as the wrestling coach (hence “Coach”), before winning an American Field Service fellowship to France. There followed a remarkable several years in Paris, where he got in with a group putting out a fledgling literary magazine called Merlin, publishing avant-garde writers like Ionesco and Genet. The story of how Dick made contact with the reclusive Beckett and eventually got him widely published in both France and America is at the fascinating heart of this memoir. And yet, while Dick would get to know almost all the serious literary stars and leading publishers of the 1950s and ’60s, he remarks in the memoir that “I have always found communication with famous people difficult” — an inhibition I can well identify with.

Seaver’s exciting but near-poverty years in Paris I can also identify with, since traveling on stringent fellowship funds of my own, I spent six weeks in Paris in the fall of 1954, part of that time living in a cramped and dingy hotel room on rue Jacob, a street on which Dick had also been living in similar circumstances. Getting funds for the next issue of Merlin, as well as dealing with its increasingly heroin-addicted chief editor, was a constant challenge. At the same time, Dick managed to complete and successfully (with honors) defend a dissertation on Joyce, while his bride Jeannette won first prize as a violinist in a Paris Conservatory competition.

The Paris years ended unexpectedly with a recall to navy duty, after which Dick, in a curious career twist, became a management consultant. However, the idiosyncratic and daring publisher Barney Rosset, who had met Beckett through Dick, lured Dick to Grove Press, which was publishing innovative and often sexually provocative work. At Grove, Dick would take part in the publication of D. H. Lawrence’s unexpurgated Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the legal fight to get it uncensored. He would be involved with similar struggles over works by Henry Miller, Burroughs, Richard Selby (Last Exit to Brooklyn) and John Rechy (City of Night).

After vivid descriptions of police violence at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, the memoir concludes with Grove’s near collapse following an ill-advised expansion. It doesn’t cover Seaver’s chief editor stints at other houses or heading, with Jeannette, their own firm, Arcade. Here, I record the only disagreement I ever had with Dick. In publishing my largely photographic book spanning half a century in this evanescent city, he rejected my cherished title, “New York, My Love, Hold Still,” for the populist New York, You’re a Wonderful Town!, hoping that would generate sales, but which I felt would put off those I hoped to attract. When I mentioned the title of Dick’s memoir to my younger son, he remarked wickedly, “He gave his book that title but wouldn’t let you have yours?”

All the same, The Tender Hour of Twilight is an absorbing read, and I only wish “Coach” were still around.

— Henrik Krogius, Editor

Brooklyn Heights Press & Cobble Hill News

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment