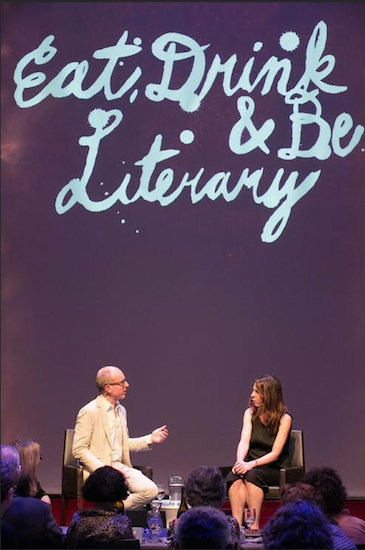

Acclaimed novelist Rachel Kushner concludes BAM’s 2015 Eat, Drink & Be Literary program

Brooklyn BookBeat

Where is the line between fact and fiction? It can be a blurry one even in fiction, where fact isn’t even fact. And ultimately, trying to know everything about another person’s history and circumstances borders on the absurd, even, suggests novelist Rachel Kushner, if that person is someone you’ve created.

“I put into the text exactly what the reader and the author need to know,” she said at a public reading Wednesday evening from her book, “The Flamethrowers,” at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM). The presentation was the last this season from BAM’s Eat, Drink & Be Literary series. “It’s not part of the creative process to know everything about the characters.”

Kushner has written two books: “The Flamethrowers,” her most recent novel, and “Telex from Cuba.” Both books were finalists for the National Book Award. At Wednesday’s reading, she chose an excerpt from “The Flamethrowers” — a story about a woman who moves from Reno, Nev., to New York City to pursue her calling as an artist. But the passage Kushner selected for the BAM audience contained no details of the 1970s art world the book chronicles, but, rather, a sea tale told by one the book’s supporting characters to the rest of its cast.