Island hopping, mountain climbing and soul-searching

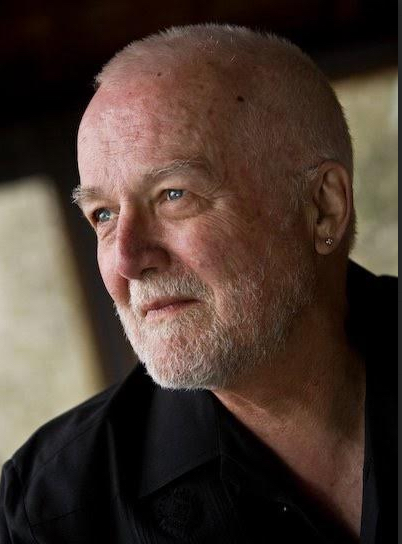

Q&A with Russell Banks On His New Travel Book “Voyager”

The arrival of a new book by Russell Banks— whether a novel, story collection, nonfiction or poetry— is cause for celebration. He is, quite simply, one of our finest writers. Even when his game is slightly off, he’s still got better stuff than anyone else in the rotation. To pay him the highest compliment that a Brooklynite can pay someone, he’s the Sandy Koufax of American writers.

My introduction to Banks was his 1980 novel “Book of Jamaica.” Part history, part confessional, the book had such an impact on me that once I finished it, I tracked back and read “Family Life” and “Hamilton Stark” and then impatiently waited three years for “The Relation of My Imprisonment.” Two years later, Banks published the novel that, for me, raised the bar to a height at which very few (Ford, Salter, Stone) could compete: “Continental Drift.” Thirty-plus years on, the book still leaves me astonished and overwhelmed. In re-reading the novel recently, even though I knew the ending, the book, especially in its last 50 pages, is like a time bomb. (Banks has written a screenplay, and at one point, Jonathan Demme was attached to direct; although the subject matter of the book is timeless, if ever there was a time for a film to be made about class and immigration, it is most decidedly now.)

Banks has now graced us with “Voyager,” a new book of travel essays. The title could not be more apropos. The terrain Banks traverses is as much emotional as geographic, as much about his past as his present. Equally fearless in exploring both, he privileges the reader by sharing his discoveries, no matter how unflattering they may be. “Warts and all” doesn’t begin to describe his candor.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.